Working with Martin Simpson

This adventure has no end point, there was no brief, no requirement for an instrument to do x. I build guitars for players, I listen to their playing and try to understand what it is they are looking for in a guitar, and then work out how to deliver that. Martin has dedicated his life to playing. He has played all over the world on the world’s best instruments. This, as I know now was the beginning of an exploration that pushed everything I thought I knew about making guitars. What if?

I’ve been fortunate enough to know Martin since I was based in Edinburgh more than 8 years ago, introduced by our great friend Ian Brown during a road trip guitar tour. It wasn’t until thirty months ago that this all started though. Martin met up with one of my clients at a gig who showed him his new Tirga Beag in Cocobolo & Adirondack. I got a call from him the next day.

I had recently completed an Ulladale in Belizean Rosewood, the most beautiful wood. One of only two sets reclaimed years ago while raking through stacks of wood stored in an ex-vet’s basement in Edinburgh with Stefan Sobell. This tonewood was just like old school Rio; its straight brown grain shimmered under lacquer and rung like a bell. When I spoke to Martin that day we agreed I’d send it down to him to try before I journeyed south to visit, so that we would have something to discuss after he had played it for a couple of months.

Between Christmas and New Year I got a call, the words spun around my head for days…. “Its great, I love it. Such an exciting start!” My days, a start, a start of what?

Down to Sheffield

The day came and south I went, so nervous I arrived at Edinburgh Waverley an hour early so I didn’t miss the train! Martin welcomed me with great coffee and chat about birds and politics, then rushed off to his studio and came back with the Ulladale. He sat, said nothing and played. In that moment, two things happened; the first, a wave of emotion that one of my musical heroes was seated in front of me playing a piece of my work. The second and this I’ll never forget. I heard all of the extremities of that guitar, the highs, the lows, the good bits and the bad bits, its limits. All this in 4 or 5 bars. Martin thought highly of this guitar, but me being the questioner I am, I pulled it to bits. Every guitar has its own character, but when you hear it laid out in front of you like that you can decide which elements you like. The question is: what would make them better, and how far can they be pushed?

At that time, Martin had just got a 00018 from the 30’s. This instrument blew my mind, you know one of those Martins that is just how it should be from back then? Imported just after it was made so in great condition due to never being dried out. So light with so much power and spit at the start of the note and then this really mature tone ringing behind it! I had never heard anything like it, still haven’t! The Ulladale had spit and we both agreed that this was important in any guitar that might visit Martin. The other thing I liked in the 000 was the fullness behind the note. It meant Martin had the richness when playing softly and then tremendous power when it was needed too; a heady combination. I also listened to him play his Sobells and other guitars including strats, slide guitars, another Martin, a Fylde. I listened and every time came back to similar thoughts on fullness of tone behind that first initial spit of power. I wanted this but I also wanted to hear definition, not metallic, brash, forced definition but a more orchestral sound.

Lets face it, I’m not going to recreate a 30’s Martin and I’m not Stefan Sobell, so where was this going to go!? Head whirring overtime, I headed home, Ulladale in hand.

The Ulladale (now sold) continues to remain a high in my building, it has the separation I like to hear in my work. There is a lot of power with a richness that you can get from high quality rosewood and a super responsive soundboard which in the Ulladale’s case was Adirondack. However, I wanted to hear all of this with even more definition, even more life and fullness.

Back to school

Being a self taught guitar maker I have had to learn what does and doesn’t work. Because of this experimental approach, I have a bank of knowledge that I can draw from when building a certain sound that I have in mind. Whether it be a very light response finger style guitar with lots of overtones and sustain, or a powerful but rich accompaniment instrument with good but not over the top separation.

The sound I had in mind for this project however, I had never tried or achieved. How would I make an instrument with orchestral fullness and definition behind a note with great separation, power and spit?

The answer is in all of the guitars I’ve made and in all of the research in sound I was about to embark on. But back then I felt that I had to start right at the beginning! You might ask, why not just push your current work? Why does it have to be totally different? My answer is you have to move away before you can come back afresh to it. It’s that “can’t see the wood for the trees” analogy.

A month passed before I settled my thoughts on the direction to go. Obviously influenced by the 000, I wanted to build as lightly as possible, stripping everything to its minimum. So, I chose single sides in old mahogany with the same for the back and neck, old spruce - German for a little warmth. I used the Ulladale’s 12th fret soundboard bracing pattern to have a constant. Materials sorted, soundboard/engine sorted; the next thing was to look at the shape.

Years ago, I built for a short time the Tirga Mhor Mk1 which was a larger version of my most popular model, the Tirga Beag. This seemed like the perfect time to revisit the model but all the variables were getting a bit out of hand. I decided to keep the Beag size and extend from the waist to the 12th fret just as Martin & Co did the other way to get the OM way back when. To my mind, shape is more important to the visual and comfort of a guitar rather than sound. Size changes sound though. If I went bigger I’d get more power and more bottom end because the soundboard has a larger vibrating area. While I wanted these things, I was aware from previous experience I’d lose definition, and my fear was that I’d lose the spit too. Two elements were key to moving forward. Increasing the depth of the Tirga Mhor to 120mm from the Tirga Beag’s 115mm. This, along with the increased upper bout size added air to the box but kept the soundboard at a width I felt I could control. At this point, it did feel like I was recreating the wheel, or in this case the 000 piece by piece, but in my mind I had to understand all of the design choices inside out before I was going to move in a direction somewhere close to forward.

The first Tirga Mhor in Mahogany went to Martin in August 17. I was really pleased with it as a start for the model. It was super light and gave us the spit we were looking for. It was really responsive and proved that the 12th fret position worked with the size and depth of the guitar.

I knew that there would be more trips south and felt real excitement in knowing that this guitar was the start. It was tangible and a different guitar to anything I’d made before, and because of the approach to designing it, I knew why it sounded the way it did.

Time to go to Sheffield again

Again Martin played, we had banter but, on this visit I listened harder to the notes. This was perhaps when we started discussing guitars without words. Mad? Guitar making is in its purest form is only opinion. It is my opinion that says, ‘remove that shaving of wood, leave that brace at that height.’ There are no rights, no wrongs. I had built this guitar using the opinions I have, and because of these it sounded the way it did. When Martin played the guitar I could hear whether my thoughts/opinions were well founded or completely off point. Like discussing politics with some one who knows it from every angle. Discussing guitars without words.

When building I thought it was the lightness that would allow the fullness of the note to come out. I wasn’t completely wrong on this one. I’ve used the word ‘fullness’ and I suppose I mean ‘chewable’ or ‘rich’ or ‘rounded’. Basically, I wanted so much that you get lost in the note’s complexities. I felt that in this guitar it was almost like there wasn’t something to give it the fullness I was after. Too little mass in the guitar to shape the back of the note.

I had also reduced my sound board curve and, listening to the guitar, I felt that the separation wasn’t as prominent because of this. I’d done this because in my head, this would increase the spit creating a faster attack, which indeed it did, but I wasn’t willing to lose the separation. Somehow, I had to get both into one sound board?!

The note sang, no doubt about that, it had a kind of hollowness to it, a dry and punchy sound, absolutely perfect if that is what you are looking for. However for myself and Martin, it was just the starting point.

On that visit to Sheffield I also dropped by my great friend James Fagan. He has owned a Malaysian Blackwood Tirga Beag for the last 6 years. His guitar was a real cornerstone on my building and when I saw it again, I was reminded of the steps I had taken back then. It was almost like I had to make this new guitar and his as one.

Leaving that day, I watched the countryside whistle past knowing it might well be some time before I’d be back. If I’m honest, there seemed like an insurmountable task in front of me. It was now September and I had to bury my head in the orders on the bench. I certainly didn’t park the Simpson project, I just needed a moment away to reflect. I had so many ideas that developing them all would take years.

The sense of community

On the 8th of January I received an email from Tania Spalt inviting me to the 2018 Holy Grail guitar show in Berlin. I instantly replied, which isn’t like me! ‘Yes.’

This was a perfect opportunity to do some serious development work on new ideas I had settled on looking at over the winter. I’d also get feedback from the guitar community.

I wanted to show 3 guitars, all with a development that would go to help the Tirga Mhor:

The first, a Tirga Beag DS1 in Malaysian with the next development in soundboard bracing. I knew how a Tirga Beag sounded so how did this change fare? It was the first Dowling Signature guitar. These are very limited edition series of my instruments, built from the finest woods with exclusive detailing that allow me to push developmental ideas and techniques.

Second, a Taran DS2 in Maple to test the beginning of the new back profile and ultimately the new Compression Braces. Again, I knew how this guitar sounded so how did this change affect.

Lastly a Tirga Mhor in Tasmanian Blackwood. The next step on the model was to return to my standard building style to see how it fared. I had bought some Tasmanian Blackwood a year prior to this build. It being dry and ready, I just couldn’t resist using it.

The feedback from people in Berlin inspired me to move forward. I came away from the show with an elevated passion for building and I really felt that I had entered into a new community, a community of builders and players who delight in new ideas and progression.

From all three of the guitars I heard everything I wanted in one Tirga Mhor. It was time to push the developments, put them all together and see what Martin thought.

Time to bring it together

Compression Braces

I’d had an idea for a new back profile and bracing for a while. As with everything, it needed to be tested and then tested again! One of the guitars coming to Berlin was a wee Taran in Maple. I used this guitar to test the new back profile. It worked brilliantly. It was difficult to make but worth it as the increased curve made for a the more reflective back that threw the sound out. Here is Michael Watts playing the Maple Taran.

Next on my list were the new compression braces. The principle of the compression braces is to maintain the cylindrical back profile but allow it to vibrate while giving a reflective surface for sound waves.

The benefits are 3 fold:

Comfort

People always say to me that my guitars are particularly comfortable because of the cylindrical back profile. This characteristic allows you to play a large instrument without it feeling too big. It feels deceptively smaller bodied as the widest part of the lower bout is also the narrowest in depth. As opposed to a rib rest that cuts the edge off, the cylindrical back profile hugs the player and also brings the playing position into a closer and more natural posture.Projection

We could go into the complexities of the vibrations of a guitar here, but let’s imagine sound as a tennis ball. If you throw that ball against a bed sheet on a washing line it will disappear into the sheet and then fall to the ground. If you throw the same ball against a brick wall, it will come back and hit you in the face! In guitar terms, the reflection of sound off this solid surface is vital in order to hear the guitar, both as a player and as an audience. The cylindrical profile of the back makes an extremely reflective surface that throws the vibrations off of the sound board, out of the sound hole, into the ears of the player and far beyond.Colour of sound

Every piece of wood has its own tonal quality and influences the instrument’s sound differently. This is where the compression braces really start to work their magic. The nature of the compression brace is to have minimal mass on the back of the guitar. This allows the back to vibrate as freely as possible across its entire area. This resonance influences the sound of the guitar, allowing the character of each variety of wood to be maximised; be it rich, earthy, bright or dry.

Happy with the profile, I needed to develop a brace strong enough to hold the shape while having the lightest mass possible. The design of these braces was inspired by the principles of archery. I used a strip of wood or “Bow” under both compression and tension because it is fixed at both ends by a non stretchable material. The theory worked, but as with every part of a guitar it was crucial to get the balance between strength and weight, with knife edge precision.

To double side or triple side?

I’ve been building with double sides for years now when I’m looking for a thicker, less hollow sound. The Triple sides do this but also make the sides even more stiff. I wanted this because the back was a new design and I needed to guarantee no movement in the sides. I also needed that thicker sound so the triple sides were a a win win. After a lot of thought, I used a Closed Cell foam instead of Nomex Honeycomb for the internal layer. I felt that having a whole surface would make it as stiff as the honeycomb but without the air cavity while keeping the monocoque construction. Like a surf board, it relies on the two outside surfaces to give the soft foam its stiffness and rigidity. This side unit was insanely stiff! Once the back was on I could tell this was going to be very different. It rang like a sound board when tapped or when the radio in the shop was on.

Neck material and neck joints

I’d been looking for a wood that sits between light stiff Mahogany and very dense and super stiff Wenge for a while. The more dense the neck wood the more focused the sound. Wenge is amazing at adding power to a guitar because of its stiffness. I wanted this stiffness for the power but I didn’t want to focus the sound too much. I had bought a board of Padauk when on a trip down south and when cutting this for inside sides I was blown away at how stiff it was but it was almost light as Mahogany. Perfect!

This new Tirga Mhor was to have a Cut-away allowing access above the 12th fret neck joint. I wanted a really slimmed down heel to maximise the neck length. Basically, I imagined the heel part of the neck inside the body of the guitar. I also wanted it to be glueless because I love a challenge and it meant any future adjustments would be very easy. The fret board extension allows for a glueless joint because it is dovetailed in, which stops the neck rising up from the pull of the strings. A great process and now standard on all of my guitars.

Soundboard

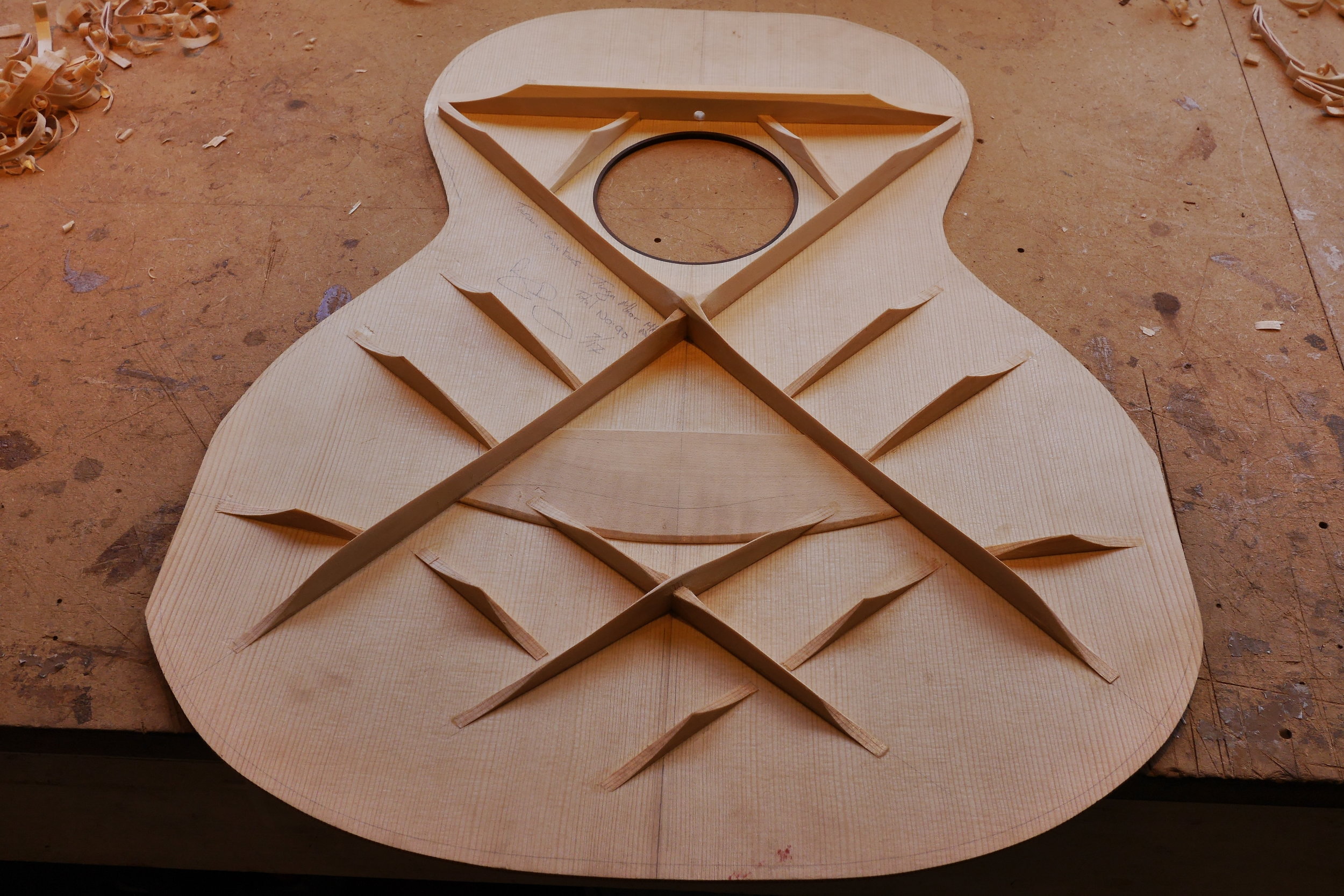

With the developments since the first Ulladale that went down to Martin on the soundboard design, an untrained eye would notice very little. But while the pattern remains very similar, almost everything else has changed; From brace size and height. Brace taper areas. The curves used. Board thicknesses. Neck angle. The list continues…

For the first Tirga Mhor DS build I wanted to use something special. I’d been sent a few sets of Swiss Bearclaw spruce by my friend/wood provider Stephen Keys. It was perfect for this build. Beautifully figured, stiff and close but not too closely grained.

A run down of this Tirga Mhor.

Back - Master Grade Tasmanian Blackwood with Compression Braces.

Sides - Master Grade Tasmanian Blackwood and Padauk Triple sides.

Soundboard - Master Grade Swiss Spruce.

Rosette - Hot Fade Crail Elm and Wenge.

Bindings - Ebano & Scottish Sycamore purfling.

Front Purfling - Padauk purfling around the soundboard.

Linings - No linings.

Bevel - Hot Fade Flamed Jarah.

Neck - Padauk with Graft and Volute. Glueless neck joint. 2 way Truss and 2 6mm carbon rods.

Fret Board - Ebony bound with Ebano.

Fret Markers - 9Ct Gold dots with 9Ct Gold Circles at 12th fret.

Frets - EVOGold wire with Semi Hemispherical fret ends.

Headstock - Hot fade Flamed Jarah with black veneers under sheaths.

Tuners - Gotoh 510’s in Gold.

Hand Carved Solid Ebony Bridge with Ebony Pins.

t. Hand cut from solid 9 Ct Gold sheet.

The verdict?

It is my 102nd guitar. When I first strung it up it was different, I could hear that.

I sent it off to Sheffield.

Martin called a month later. “I really think you need to hear this, Rory”, were his words.

Seated again in front of Martin I heard the guitar, laid out in full before my ears. Did it sound as I had imagined? It was bloody close!

“Rory’s work has been on my radar for several years, I have always enjoyed watching him chase ideas and improvements in his building.

I enjoy my friendships and working relationships with some of the best guitar builders on the planet and was very pleased to share ideas with Rory and show him instruments.

A 1931 00018 Twelve Fret and a Sobell Steinbeck conspired with Rory’s ideas and out came this very fine instrument which is it’s own beast!

You can hear it on my forthcoming CD.”

This adventure has influenced everything about guitar making for me and continues to push my work. I have met so many wonderful builders and players in the last 2 and half years that I would like to thank for all of their support, kind words and advice. Most of all I want to thank Martin for pushing me and always being excited about the guitars I’ve shown him and for questioning my opinions without saying a word! We are still asking, what if?